Once again out of the GDR …

(GDR means German Demokratic Republic, the former socialist East Germany…)

Off to Southeast – Europe Part 1

The year 1989 is for me (as a east german youngster) the year at all. (Unfortunately, the hangover followed after the thrill in 1990).

The events literally rolled over, practically every week there were somehow new developments and twists. At the end of May, I unexpectedly received my notice of termination. After dropping out of university, I had been employed at the post office in telecommunications, and I had also wanted to start an apprenticeship there. But after I had left the „Free German Youth“ organization (Freie Deutsche Jugend – FDJ, the east german socialist youth organisation, more or less obligatory for all young people) „unnoticed“ at the end of 1988 (the district leadership had turned a deaf ear) and had gone on a slowdown strike before Easter, when I was lent to a postal customs office to „tear open west german packages“ for control, the party-leaders in the telecommunications department were probably fed up with me.

At the beginning of June we held a self-organized „youth weekend“ in the church parish with over 100 guests from many other church youth groups, a complete success. One weeks later, I was present at the first officially unauthorized street music festival in Leipzig, when police and Stasi (secret police) hunted down young people with musical instruments in their hands. The very next day I led an environmental group by bicycle through the forest to Börln on the edge of the Dahlener Heide, where an environmental church service was held in protest against a planned new nuclear power plant.

At the end of June, I went with my church youth group for a long weekend to Marieney in the Vogtland, as a thank-you, so to speak, for all the work on the youth weekend four weeks earlier. I had contacted a young, committed pastor there, with whom we could stay overnight with tents on the parish grounds. On the way there, while changing trains in Leipzig, we were circled by quite a few inconspicuous gentlemen with one hand in a Perlon bag (secret police men). On the train to Plauen, the „Trapo“, the transport police, checked us. But that was „normal“, because behind Plauen the border area to west germany and the iron curtain began.

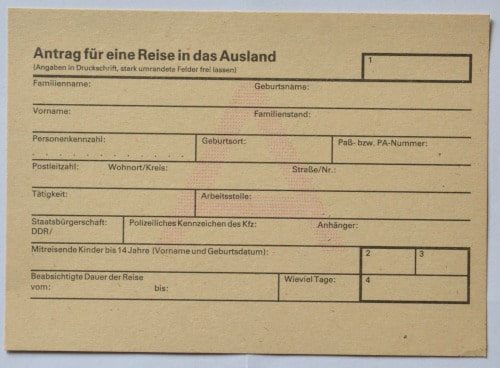

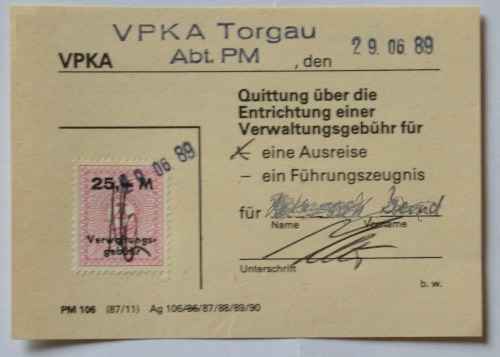

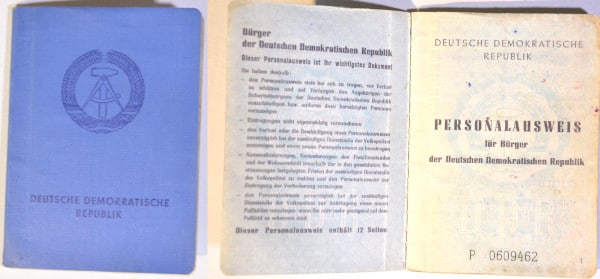

In July, I had the always unpleasant appointment with the police, registration department. But it went without incident. It was already about my next trip. The GDR declared officially „visa-free travel“ with the european socialist brother countries in the neighborhood, but in practice it was a bit more complicated. Only in Czechoslovakia, every GDR citizen with the correct identity book could simply drive off, at the border came the stamp in the ID – book (Personal – Ausweis, short: PA), done. (Who had only „PM12“, the substitute identity card, which was prescribed to some also due to coercive measures, could not travel anyway). For the other brother countries one had to apply at the police – registration office for a so-called „Reiseanlage zum visafreien Reiseverkehr“ (travel annex for visa-free travel), which was presented and stamped at all the borders together with the identity book. I had made the application a few weeks before and I could now pick up the paper.

Now I had to visit the State Bank branch. We normally got the Czechoslovak crowns at all the savings bank. For the exchange of all other currencies we had to go to the State Bank. And there was a strict limit on how much money was paid out for Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. On the one hand, there was an annual maximum amount, and on the other hand, a fixed rate for each day of travel. This was entered in the identity book (PA). Since that was quite a lot of stamps, a leporello was pasted into the PA, where there was enough space for all the entries. Usually, the daily rates for Bulgaria, Romania and also Czechoslovakia were reasonably sufficient, if one traveled sparingly. For Hungary, which had a freely convertible currency with the Forint since a few years, the money was quite scarce, about 31 GDR marks per day. Especially since there were some sought-after Western goods in the country, such as records, jeans or the BRAVO youth magazin… and they were very expensive. This was also due to the exchange rate – one GDR mark cost 7 forints. For one DM (west german Mark) it was 25 forints.

O.k., the official preliminaries were thus completed. The post and telecommunication branche gave me once again a free summer (of course, I had no intention to go back to work somewhere before September – if they give me so generously the main – travel time off). And I had some special ideas this time, how I wanted to be on the road. Inspired a piece of the popular DEFA° – film „… und nächstes Jahr am Balaton“ (…and next year at Lake Balaton), which brought so the typical GDR- Blues across. In it, a family wanted to take the train to Bulgaria with their daughter and her ever-so-slightly melancholy boyfriend. But they quarrel already on the first kilometers and so in the end everybody starts the journey in his own way – among other things as a tramp – tour. From this the film plot develops as a road – movie of the East. °DEFA …. east german film company, situated with film studio’s in Potsdam – Babelsberg*

I had planned to set off alone that summer. The first time on such a big tour, to be independent, to organize and decide everything myself. And to get involved with the coincidences along the way. Okay, I already knew that I would not be so alone – every summer a huge stream of GDR citizens moved to the southeast. Many went to Czechoslovakia, a large part to Hungary, to experience a piece of the „West“ there. (But this was rather a masochistic pleasure, because the Hungarians knew very well to distinguish whether it was East – or West – Germans and the „quasi-West experience“ already because of the exchange – rate for East Germans was more limited to „enviously watching“).

Above all, I wanted to hitchhike large parts of the route. In order to be more independent, I sewed me in the weeks before a kind of duffel bag. Compared to the rather bulky Kraxe (backpack) with external aluminum – frame I hoped to be able to get in and out of cars easier and faster. I also wanted to do without a tent. The smallest GDR – tent was the „Fichtelberg extra“ and still weighed 3kg. Everything was too much for me. I had cut and hemmed a DeDeRon – fabric (the GDR nylon) as a Tarp (tarpolin) and tried to make waterproof with impregnating agent. Later I had to find out that this did not work at all. Just good that the summer was quite dry. My first self-sewn „Tarp“ was therefore nothing else than a leaky, little warming blanket. But the real luxury was a down sleeping bag, which was sewn for me by a small private entrepreneur in the Vogtland.

On my short farewell round through the city I realized that the duffel bag was not such a good idea. Wears just totally uncomfortable. Half an hour before my bus drove, I took the good old Kraxe out and quickly repacked everything. There fit even my rolled up stiff insolation matress under it, which I have cut to „Reichsbahn° – compartment door dimensions“ and drastically shortened (which were sold as „repair – mat“ for car mechanics and are quite robust, I take today still sometimes). ° Reichsbahn … east german railway

Then in the middle of July it finally went off. First goal was of course Dresden main station. At that time for me the „gate to the world“, so here began the „rear exit of the GDR“. I had a train ticket to Bratislava. Unfortunately, right after leaving Dresden, the border controls always started. That was the most unpleasant part of the travel – 1 1/2 hours of sweating. So far I had been mostly lucky and the controllers left me alone. But I have also experienced how others were controlled like that. Once it was the turn of a young girl who was the victim of a customs aunt (the women were usually extra nasty). The bag was dumped on the seat by the customs lady in front of everyone – with everything that is in the bags of a girl.

This time I was due as a young person traveling alone. The inspectors were already suspicious that I only had a ticket to Bratislava, but a visa annex up to and including Bulgaria. But I was able to show a return ticket from Bulgaria and told them something about friends who would take me in between. I still had to unpack my backpack. The inspectors were especially interested in my calendar and the part with addresses. I had not been aware of that until then. Presumably they were also looking for Westerners or contacts and indications of a possible intention to escape.

After the first one had seen my backpack contents up to the last corner, I was allowed to pack again. Five minutes later we were sent out of the compartment into the corridor – now the compartment was disassembled. Seat backs were removed, ceiling panels were aired and a mirror under the seats was used to look into all corners. But he found nothing and left. Shortly thereafter, another from Czech border police came, looked at all the paper again and checked my bags. In Decin the spook was finally over and I was out. Out of the GDR.

That was always a moment of inner celebration. Of course I was aware that the exit still only went „on a long leash“ and also Czechs and Hungarians always had a sharp eye on the GDR – citizens. But nevertheless it was enough for a feeling of being a lot more free there than at home.

Now the train rolled through the Czech Republic. After two hours, we reached Praha Holesovice, the international train station in the north of Prague that had been expanded a few years earlier. But this time I wanted to go further. Much further. Night was falling. Glad to be on the railroad and far from the confining GDR, I made myself comfortable in my seat.

In the next morning I reached Bratislava, the capital of the Slovakian part of the CSSR (Czechoslovak Socialist Republic). One year before, on an Easter tour to Hungary, I had already gotten impressive views of Bratislava from the train as it passed through, and now I wanted to take a closer look at this city at my leisure. The location on the Danube with the imposing Danube bridge conveyed a very modern character. But there were also some restored historic streets, which left an impression of the long history of the city. As I so searching and photographing strolled through the alleys, a man around 40 approached me. He had observed me and concluded that I was interested in history. After we had eaten something together at a snack bar, he suggested an excursion to the nearby castle ruins of Devin. It had only recently become accessible again, had just been renovated and was the new pride of the inhabitants of Bratislava.

The trip was also not very long, an extended city bus – line brought visitors directly to the forecourt of the castle. So I took the opportunity and got on the Ikarus – articulated bus with Pavel. What was not clear to me – the castle ruins stood directly on the Danube, on the other bank was already Austrian territory – behind the iron curtain. Shortly before the destination the bus had to stop – a control post. Those were exciting minutes for me, because here the border area began. Uniformed men with AK47 submachine guns over their shoulders were walking around outside. Slovaks were allowed to enter the castle, but what about GDR citizens. Would I be accused of trying to escape? Pavel reassured me that this would not be a problem, the castle had been open to the public for a few months. The guards at the barrier also only briefly looked into the bus, the stop came more from the cars in front of us. On a large visitor parking lot we left the bus and walked up the hill into the castle complex. The enthroned very impressive above the Danube on a ridge. This contributed to an overall picture worth seeing. However, a little inner tension weighed on my shoulders the whole time.

In any case, Pavel was proud of his leadership and accompanied me the whole day. Since I had no place to stay in Bratislava, he took me home in the evening without further ado. However, we had to drive to Pezinok. There he had a small one-room apartment. I slept in the kitchen with a sleeping mat on the floor.

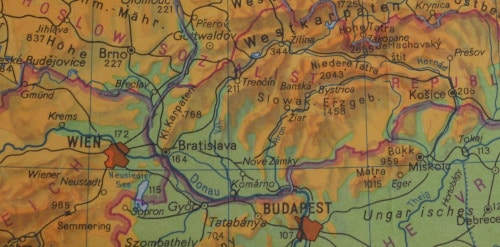

The next morning I said goodbye to Pavel and thanked him for the many impressions and the hospitality. Then I started my „big adventure“ – I wanted to hitchhike. This was more difficult than I thought. Actually, the plan was to cross the Danube in Bratislava and from there to the nearby border crossing Rajka to continue hitchhiking right away in Hungary. But from Pezinok it looked better to get a few kilometers further east in Slovakia and then cross the Danube in Komarno or Sturovo. However, progress was slow.

One or two Slovakian passenger cars took me a few kilometers. Then once a truck. Then I stood forever on a highway, where the typical „njäääng“ sounded in my ears – Trabis (short nick name for the east german Trabant car°) on their way to Hungary. East German license plates, all packed to the hilt with camping gear, canned food (with limited exchange of forints, it was better to take all the food for the 2 weeks of vacation, then maybe one or two more jeans were in the shopping budget) and the whole family.

° the TRABANT car 4 month later became very famous as a symbol of the new mobility through the iron curtain

A work colleague, who restored russian Moskvitch cars with his father-in-law in his spare time, once told me how he fills gasoline at the last gas station before the border on the Hungary tour. The goal – to get as much fuel as possible to avoid refueling with the scarce Forints. The tank in the Moskvitch is in the back, the tank opening hidden under the license plate. Of course, this car is also packed and hangs down low with the rear. Since the tank is thus at an angle, an air bubble forms at the front edge – wasted tank space! So he drives up to the gas pump and unpacks the jack. He puts it under the trailer coupling and uses it to bring the car into a horizontal position. Then he fills up the tank and closes the filler cap. (The fuel filler neck is also a filling reserve). After paying, the jack comes off and off he goes.

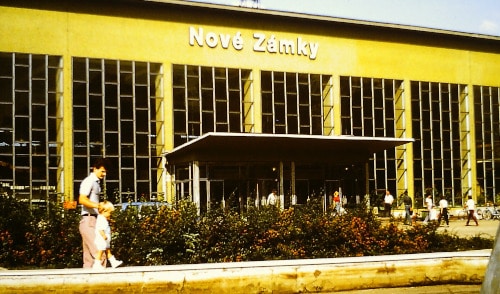

When once again one of the Slovakian Skoda cars stopped, I finally reached Nové Zámky. Now that was not such an exhilarating result. Well, border areas are always difficult.

I am a bit sobered for the time being. A decision has to be made. To speed up my journey a bit, I decide to go further by train. It’s not that expensive – the socialist brother countries have their own fare system, which makes train travel across the borders a very inexpensive pleasure. So I scrape together my Czechoslovak crowns and order a ticket to Ruse at the train station in Nové Zámky. Ruse is in the north of Bulgaria directly at the border to Romania. This saves me hitchhiking through Hungary, where GDR citizens are often regarded as second-class Germans anyway, and through huge Romania, where there are few cars and many poor people who don’t drive long distances.

The woman at the counter tells me that it takes her about 1 – 1.5 hours to get the ticket ready. It is all manual work. With the fingers in different course book pages for the necessary rail routes the tariff kilometers are picked out and added up. In addition, some intermediate stops and possible border stations are noted, so that the fare frame appears on the ticket. And then the kilometers are converted into the price. With carbon paper and ballpoint pen, the ticket form is filled out. A carbon copy then remains in the ticket office as proof. The ticket itself is stapled into a red envelope booklet made of reinforced cardboard and validly stamped with the counter stamp.

So I stroll around a little in the city. Nové Zámky is indeed „new“ – I don’t find a historical center, but lots of real socialist prefabricated buildings and other modern buildings. Not exactly to my taste. The station’s reception building is also rather a large, sober, functional building. On the forecourt there are a few borders and a fountain, all nicely rectangular. But the water provides some freshness in the summer heat.

In the late afternoon, there is still a train via Budapest. So with my ticket I can now travel on a bit „accelerated“. A small idea drives me forward anyway – in the next week a group of friends in the church youth starts for the Bulgaria tour to Sofia. By rule of thumb, I could make it and intercept the guys and especially gals at the train in Sofia. We could then do the mountain hike in Pirin planned after that together. With hitchhiking I would probably never have managed that, but now this meeting moves back into the realm of possibility.

I don’t stay long in Budapest. It’s late evening and it’s already getting dark. Sure, I could find a place to sleep somewhere, maybe on Margaret Island. But why should I stay in the city, if I want to continue the next day anyway. I board a suburban train heading east and drive out into the country. In the small town where I leave the train, it is already pitch dark. A few dogs are barking, but otherwise everything remains quiet. I run only a piece out and look for me a bush, behind which I spend the night.

The other morning we continue to the train station and then to Szolnok. A few photos of „typical Hungarian country idyll“ with sunflowers and dung heaps, and off. In Szolnok I was the year before with a friend, who wants to study at the film academy and therefore takes photos everywhere, what the stuff holds. There was a dance festival over Easter, where a breakdance group from our region also wanted to participate. Breakdance had just become really popular in the East, to which the US film „Beat Street“, which was also shown in GDR cinemas from 1985, contributed.

Groups were formed everywhere and the breakdance wave rolled through the Eastern Bloc. However, only a small part of the dance festival turned out to be a breakdance event. I don’t know how many times I heard Jackson’s „Thriller“ that day alone. It felt like every second dance couple had chosen this music for their show, and by the evening it was already pouring out of my ears…

On the stopover in the summer of ’89, however, I only made a few rounds through Szolnok, sat for a while at the Tisza, remembered the dance contest the year before and waited for the appropriate international train that would take me further.

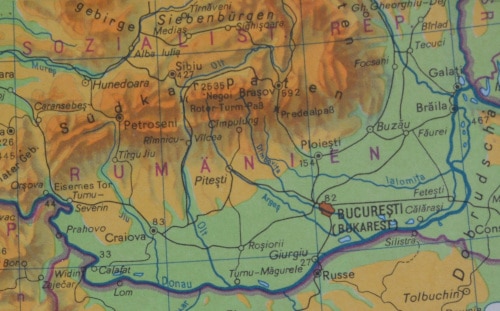

Actually, the direct way from Hungary to Bulgaria is via Yugoslavia. But this is considered in the GDR as „renegade“, because the Tito socialists have sought their own way with some distance to the Soviet over – brother and allowed themselves a quiet opening to the Western European capitalists. Thus, the vacation paradises on the Adriatic were reserved for currency-paying Western Europeans and the Iron Curtain ran north of the border separating Hungary and Romania from the nevertheless Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia.

For GDR – citizens this meant on the way to Bulgarian summer joys the far detour over the rather unloved and impoverished Romania. This country seemed to me sometimes rather like one of the South American steppe countries. Especially in summer, when the sun glowed over the Puszta. Comparisons came to me, for example, with images from the movie „Green Ice“, in which corrupt policemen hunt for smuggled emeralds in a South American country – in union with a mafia of the local gemstone – baron.

In the Pannonia – Express I had once experienced how the train rolled from Hungary into the small border station at noon and stood there in the sun for over an hour. (There were no air conditioners, open windows were used for ventilation). The Romanian border guards, who took a lot of time with the control, came to GDR – travelers always with the question: „Have weapons, ammunition, narcotics…?“ Whole compartments were screwed apart, the washrooms and toilets anyway. Dogs had to run under the train and on the roof and sniff out all the cavities. In between, the guards gathered next to the train for roll call to receive the latest order of the day. We sat in the hot train, waiting for the onward journey, the crickets chirping… With the blue ID-book of the GDR citizen, this was all rather amusing, since we obviously passed as harmless and remained largely unmolested.

The train I boarded in Szolnok in the late evening hours, however, was from Poland and therefore largely occupied by Poles. When we reached the Romanian border in the middle of the night, it wasn’t so funny. I stood as usual with my blue booklet at the side and was hardly looked at, but with the Poles all luggage was checked. And all that in a rude tone and with some shoving and yelling.

Since the Poles have had to deal with a corrupt government and enormous impoverishment over the last twenty years, they have developed a good sense of what might be feasible to do small business with. No huge profits, just ways to make everyday life a little more bearable or, as in this case here, to be able to finance a vacation at least to some extent. And so the Poles had a whole lot of spice packages with them, which they wanted to sell under the table in Romania. In any case, significantly more than the personal needs. Unfortunately it was then in such a way that the Romanian customs skimmed the profit rather already in advance. What did not go off without tears, indignation and rage.

On the other morning the gloom was gone. The Poles, who are always very sociable and hospitable, invited me to join them for breakfast and we spent a good time together.

Most GDR citizens passed through Romania rather quickly. Despite wonderful landscapes, poverty was tangible everywhere. When the colorful express trains from faraway countries entered the stations, people came running from everywhere to beg. Filthy children in torn shirts and worn shoes shouted „Guma, Guma!“ for gum or candy. The trains certainly seemed like messengers of prosperity to the people here. Many a tin can changed hands, many a bar of soap made the eyes sparkle. But it occasionally happened that children threw gravel stones into the windows when their begging fell on deaf ears.

Two valleys are still impressively in my memory from Romania. When the train entered one valley, the images outside the windows changed. Everything was black – the corn in the fields, the leaves on the trees, the houses, the roads and cars, the people on the platforms, and sometimes even the laundry on the line. The place where the trains stopped was called Blaj. That already sounded like lead to me (in german „Blei„). And then the train passed a factory at a walking pace – a huge black corrugated iron box, through the tiny windows you could only see dim sparkles illuminating the factory halls. And above it towered chimneys, from which rose a single endless column of black smoke. Only when the train left the valley did the colors become friendlier again.

Elsewhere there was another valley, only here everything was dusted with white. The sight was somewhat more pleasant, but whether this dust was really so much better than the black of Blaj, I cannot judge.

Nevertheless, there were some, especially young people, who also found their summer destinations in Romania. The Fagaras Mountains were always high on the list, despite stories of feral dogs that roamed there in large packs. Or also the Danube Delta, an Eldorado for water hikers. I wanted to get to know the Transylvanian city of Braśov – with the old german name Kronstadt – in the summer of ’89. I have already passed through it several times.

Therefore I left the train there. The station forecourt frightened me. Everywhere garbage lay around, everywhere heaps of sh… -. A functioning station toilet does not seem to give it. Actually I wanted to sit down first of all somewhere to eat something, but that passed me at this sight immediately. The surroundings didn’t look very inviting either – prefabricated buildings – high-rise buildings, a trolley bus line, streets with some stinking cars and a few horse-drawn vehicles. But nothing that I would have liked now. A cinema showcase with a poster for a Rocky movie. In this, the socialist countries always differed a bit. What was shown in the cinema in some countries was frowned upon or even forbidden in others.

I was already on the verge of looking for the next train at the station. Brasov is located on the northern edge of the Carpathians, from here it goes steeply uphill by train to the station Sinaia, which is such a noble – recreation place in the mountains. Then comes the Carpathian breakthrough at the Predeal pass and then it goes south again steeply downhill to Bucharest. This means that the Carpathian Pass forms a kind of funnel through which practically all international trains to Bulgaria have to pass. In this respect, there is a chance several times a day to get away from here quickly.

All right, so my departure should not be a problem. But I remember to have heard from some that Kronstadt is definitely worth a visit. This soulless desert of prefabricated concrete slabs in front of the train station can’t be meant by that.

And so I make a second attempt. First I try to orient myself. To find out in which direction the city center is located. If no city map is available, I try that on the basis the announcements at buses, timetables or what else can help. When I have a guess, I start walking. And indeed, the scenery changes. I reach some streets with old town houses worth seeing. Although much is dirty and somewhat run down, but overall the picture is improving.

The streets are now largely tidy and the houses have their charm. There are large gates between the houses, and behind them are leafy courtyards with vine trellises on the walls. The cars that drive around here are mostly decrepit and rickety, but not very numerous. Around the market I even discover some freshly renovated houses, the square is covered with natural stone slabs and quite attractively designed. On benches and next to the flowerbeds sit families, old and young people. Most of them look simply but neatly dressed, not like in the station area. Old women wear headscarves, the older gentlemen are in white shirts and jackets. Next to the town hall is a fountain with a wrought-iron decorative grate.

Behind the market, on a corner of the market, rises a large church – the „Black Church“ of Brasov. As I approach the church building, I hear organ music from inside. As if to welcome me! I quickly look for the nearest entrance and settle down on one of the pews in the nave. One of the organists has scheduled his practice session for just the right time, and I enjoy it. A sublime feeling arises – I am alone on the road, in the middle of Romania, and now I may experience the sound of this beautiful Buchholz organ of Kronstadt.

The Black Church of Brasov is a German church building of the Transylvanian Saxons (former german seddlers), which was completed around 1477. During a great fire in 1689, the church was also largely burned down, only the surrounding walls were still standing. Because of the blackening it was called „Black Church“ from then on.

When the organist has finished his retreat, I leave the Black Church and roam the streets around the market. It is already noon and a feeling of hunger makes itself felt. I have to see what I can find. I have already seen a few relatively full restaurants. Maybe there’s a place for me and also something nice to eat. Well, a kind of dumplings, that works.

In 1989, I am currently in a „conversion phase“ as far as food is concerned. I decided to become a vegetarian. But not just like that – today the last time meat and from tomorrow only vegetables. That’s a bit difficult in real socialism. Grotesque, isn’t it? Unfortunately, for some fellow citizens the availability of sumptuous meat meals is the measure of the social condition. When people complain about something, it’s mainly that the butcher’s store again only had greasy chops and no fine fillets… To satisfy this growing demand, but certainly also because a lot of pork can be easily hawked to the West for hard foreign currency, ever larger pig factories were built in the GDR. Soulless factory farming. With stinking consequences. The amount of slurry is getting bigger and bigger and can no longer be spread on fields in a sensible way. The largest pig fattening plants therefore simply pump a large part of their slurry into the forest – and thus cause their own local forest dieback.

In church circles, in the newly emerging environmental groups and at church conventions, we are discussing these issues more and more frequently. For me, the consequence back then was already to eat less meat. And since I also wanted to be a role model, I simply wanted to gradually stop eating meat altogether. In addition I wanted to learn to cook vegetarian dishes and to create with tasty variant-rich meals an alternative to the meat pot – monotony. Thus – renouncement as enrichment experience! Therefore also my parting on rates. Well, and for the time being still as compromise, because the catering trade on the way rarely has reasonable meatless alternatives in the offer.

Now I sit in the circle of the numerous Romanian guests and soon the first questions come. I stand out – first of all dressed clearly different, then with my long hair, and besides I have a „Kraxe“ backpack and camera always with me. For the Romanians this is a rare opportunity. Under the last communist leader Ceaucescu, the country is much more closed off than the GDR. Romanians are hardly allowed to leave their country and only a few have enough money to do so. They are also forbidden to host foreigners in their own homes – even the „socialist brothers“. So they take every opportunity to talk to foreigners and get some uncensored first-hand information.

Kronstadt is located in Transylvania. This is the settlement area of the Transylvanian Saxons. They settled here centuries ago and have strongly influenced the culture of the region. Isolated from Germany, their German language has developed a little independently. In the eighties, however, the socialist government under Ceaucescu increasingly pushed this ethnic group out of its old culture. Whole villages were destroyed, the village communities dissolved and the people resettled in prefabricated buildings. Cultural traditions are suppressed, language, festivals, customs are more or less outlawed. The Black Church is basically a German church. It is tolerated as a cultural monument, but community life suffers from the resettlements and the general state repression of churches and religious communities.

Among the guests is another foreigner. I meet Ottar, a young Norwegian who, like me, is traveling here and wants to explore Romania and the Eastern Bloc. This is now also a surprise for me. I feel the same way as the Romanians. We spend a few more hours together in Brasov until Ottar leaves for his train in the evening.

Towards evening I also meet a few other East German travelers. From them I learn that they want to camp above the city wall later. Since I still have no real plan where I want to spend the night, I get a description of the way there. I’m plenty tired, especially since I spent the last night on the train and the exciting story with the Romanian customs has long provided insomnia. So I stroll through the streets towards the old city wall. The last meters are park-like. A rising path leads out of the city and probably further into the mountains. But I don’t want to go that far today. To the right, an embankment falls away, then a piece of meadow follows and on the other side are the remains of an old city wall. Behind it is the old town, the Black Church towers over the top of the wall not too far away. Despite the proximity to the city, there is not a soul on the road here.

First I settle down on the embankment and sit for a while. I must process the many new impressions first. As me then the tiredness overcomes, I roll out my sleeping mat and my sleeping bag and simply lie down at the edge of the meadow.

The next morning I wake up quite early. Next to me is a tent. The other GDR tourists have set it up during the night, I didn’t notice anything. When I listen to the stories that are told in the GDR about Romania, after that I could be sure that I would be robbed here. The night would have been the best opportunity. But since I left the station, I have never once had a bad feeling in that direction. Everyone I have met since then has been friendly, curious and helpful.

Today, I’m off to Bulgaria. I had roughly memorized the trains with which I could continue. So after breakfast and a few morning rounds through the old transsilvanian Kronstadt I make my way to the train station.

There I meet another East German family. A relatively young couple with a son of 10 or twelve years. We immediately occupy a compartment together in the arriving long-distance train. In Romania there is a problem. All express trains require reservations. But none of us has a reservation. The compartment is also empty, but that doesn’t matter. I’m already expecting that there will be some kind of trouble. When the conductor comes, however, the woman makes it clear to me that I should not worry. She will take care of it for all of us. So it happens. Of course, the conductor first wants to puff himself up and make himself important and punish a serious violation of the transport rules of the Romanian state rail company. But the very lively woman immediately takes him in hand, sweet-talks the poor guy by every trick in the book, puts a small packet of coffee in the pocket of his uniform jacket, and that’s really the end of the problem…

From Brasov, the train continues to climb uphill. The long train winds in serpentines into the heights of the Carpathians. Torrents come out of side valleys and merge with the river course next to the railroad facilities. Almost at the highest point, the train stops in Sinaia. Here there are no begging children on the platforms. From the train you can see a friendly park and spa hotel-like guest houses. High mountain peaks rise into the blue sky all around. Winter sports facilities duck into the slopes, a ski jump rises above the mountain forests. The few people getting on and off are well dressed and carry large suitcases.

After the descent, the railroad line climbs even more. High rocks pile up next to the pass track. This is the Carpathian breakthrough. Afterwards, the train goes downhill on the south side in many serpentines. Here the train must be constantly braked. It smells of the glowing brake pads, the colorful wagon snake winds around curves again and again. Sometimes right next to a rushing mountain stream, sometimes further away over broadening valley meadows.

When the train reaches Ploiesti, all the brakes are checked first. Railroad workers walk along the cars on both sides, a long-handled hammer in their hands, on which several large washers are still attached. With the hammer, they hit the brake devices and check the play. Several of the brake pads are replaced right away. This happens with every train before it rolls through the Carpathians and afterwards. Between the tracks are whole piles of brake blocks, new ones and also completely ground down ones.

Towards evening we reach Bucharest. It is already dark. Even at this station, the poverty is palpable. Especially because the lighting illuminates the platforms only very dimly. Compared to all the other stations I have passed in other countries capitals, the one in Bucharest is the darkest. Simple passenger trains are even completely in the dark, without lights. The batteries are missing in the carriages. There is light only when the train is moving and the axle generators are producing electricity.

From the „sao general“, the great communist leader of the Romanians, we keep hearing horror stories. (For big red propaganda – banners is apparently enough money there – and there is always paid homage to the „sao general“ – we read there only „sau-general“ – in german ‚pig-general‚) Thus in Bucharest a whole quarter is emptied and blown up, in order to create place for the gigantic palace of the small dictator. The German-born Transylvanian Saxons and the Banat Swabians have been trying to leave the country for years. That Ceaucescu would be hounded out of office by his people barely five months later, in December 1989, and, sentenced by a summary court, shot, was probably not suspected by anyone at the time.

But now the passage through Romania is almost done. Bucharest is already in the great Danube plain. The river forms the border between Romania and Bulgaria. Here it is already enormously wide – otherwise only the Saxon Elbe used to, that is times a river of completely different dimensions. It is four times wider than the Elbe. However, this time it is already dark when the train crosses the Danube over the „Bridge of Friendship“. This is an old iron lattice bridge with two levels. One level for the railroad, the other for the road connection. This is almost the only passage between Romania and Bulgaria. Far to the west there is a ferry, from Calafat to Vidin. And somewhere further east there is a second bridge. But this one is more interesting for tourists who want to go to the Black Sea.

Just after the bridge is the Bulgarian border station Русе (Ruse). My destination of this train trip, my ticket from Nové Zámky ends here. Tomorrow I will hitchhike through Bulgaria from here. I am very optimistic about this. In the years before I already hitchhiked in Bulgaria. And that always went well. But now I have to pass the border control. In Bulgaria this was never a problem – a short look into the identity booklet, a stamp on the „travel annex“, done. The inspectors also look quite harmless – white shirt, hardly recognizable as a uniform, sleeves rolled up, friendly and almost inconspicuous.

Then I enter the station concourse. Since it is about 1 o’clock in the night, I look for the waiting room. It is quite full, but I find a place opposite the entrance door. There I settle down, I will sleep like many others here on the floor. And tomorrow I start my journey across Bulgaria to Sofia.

End first part, if you are curios about the continuation in Bulgaria, click here! 😉